When I was 12 years old, my mother took my sister and I to a concert at Carnegie Hall. I can’t recall any notes, but I can feel the distinct impression given to me by my mother that this was an event to be remembered.

After all, we were in Carnegie Hall.

The prestigious name chimed with the force of a dozen woodwinds. At 12, the Carnegie of Carnegie Hall was a generous man whose great hall inspired generations of musicians.

Yet it is Pittsburgh, not New York, to which Carnegie owes his powerful fortune. At the dawn of the 20th century, the second industrial revolution beckoned a convoy of entrepreneurs to the city, riding the waves of petroleum, aluminum, and steel to the crests of fortune. Backed by the American dream, they built factories and turned black soot into gold, and between 1830–1930, the city housed more millionaires than New York City.

When the depression hit, many of the financial fortunes of these hopeful riders came crashing down. But for a powerful few, their legacies continue to swell: corralling a new era through music halls, universities, art museums, banks, and libraries etched with their names.

Heinz. Mellon. Frick. Carnegie.

It’s remarkable to me, then, that until I decided to move to Pittsburgh 9 months ago, I could tell you very little about the city from the top of my head. I could rattle off facts about the gilded age, I could name a golden-haired, harp-playing friend who attended Carnegie-Mellon, and I could even recall that the Steelers were from Pittsburgh. Yet the identity of Pittsburgh remained a vague idea jumbled up with Pennsylvania and Philadelphia.

In this pre-Pittsburgh life, I was quite preoccupied with ‘big picture’ concerns (never-mind an old steel town). Towards the end of my undergraduate career, I wholeheartedly pursued the buzzword technology concerns of the day (Big Tech Monopolies, Robot-Revolution, etc.) endeavoring to tackle the problem from various angles: writing for New America’s think tank on Open Markets, researching how to fulfill the skills gap waged by AI, and even joining Google’s legal policy team.

Instead, and quite unintentionally, I dove headfirst into the problem.

I landed here, in Pittsburgh, working for a startup on the front lines of a new industrial revolution. In Steel City, we work around the clock to bring the old world up to speed through our Industrial “Internet of Things” platform. As a product manager, I spend my days meeting with trucking fleets and walking through factory floors, brainstorming with former industrial titans on how to bridge the gap between their world and the future.

My job has taken me to places more exotic, in my world, than St. Tropez. I have walked a factory floor in Lima, Ohio and talked to a worker who spends 15 hours a day making a piece, for a piece, for a piece of a car (the same one, each day). I have pulled an all-nighter in Bigley, Pennsylvania observing a nightly truck-planner at work. Last week, I worked on routing-algorithms with an oil and gas fleet to maximize their efficiency (…revenue). For someone who previously defined her identity as an environmentalist, it has been a tremendous exercise in empathy.

A few weeks ago, at an Arby’s truck stop somewhere in Toledo, OH, following a factory visit, I looked up at the lone TV on the wall. Obama was giving a speech about climate change, and the necessity for all of us to band together to fight it.

How can that message possibly resonate with the people working every day, around the clock, for a minimal salary, to make sure our stuff gets made, and then get delivered to our door in the 2-day Amazon prime-window that we have come to expect as consumers?

4 years of a liberal arts degree in Political Science gave way to one political truth: we don’t need narratives, we need radical technology…and a paradigm shift as consumers.

A few weeks ago, members of our team attended the bi-annual technology career fair at Carnegie-Mellon to recruit software developers. Carnegie-Mellon, aka the philanthropic love-child of Gilded Age 1.0, has developed a name for itself as the premier computer science program in the country (1st Undergrad, tied for 1st Masters with MIT, Stanford, and UC Berkley). Undergraduates, and graduates flock to the steel city for a chance to join the elusive sphere of technology. Yet only about 5% of these graduates stay in Pittsburgh for their careers, and I can see why. Who wants to stay in the old-world when a new one is beckoning from beyond?

It was my first year at the career fair, but my coworkers had been through the shtick before.

“Everyone will rush to Google/Microsoft then slowly spread out to the other companies as the day progresses.” Notably, Amazon wasn’t even there — they had their own separate set of rooms to recruit students.

They weren’t kidding — after two hours we finally got our first prospect. As we roamed the Gates Center for Computer for Science during lunch, I was struck by the legacy: the changing of the guard from Andrew Carnegie to Bill Gates, memorialized in buildings meant to inspire the next generation of young minds to pursue their fortunes.

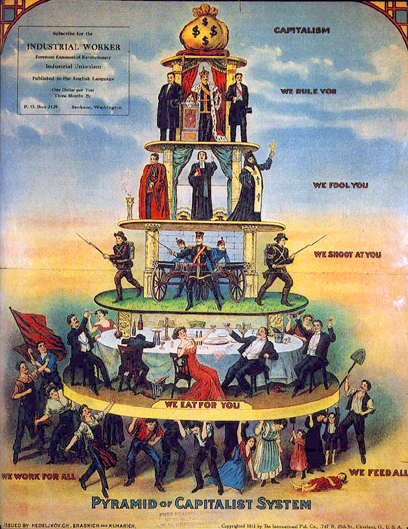

Big Data, AI, Machine Learning have replaced coal, oil, and steel — and a similar group of billionaires hold the keys to the castle.

As it was at the dawn of the 20th century, the 21st has brought unprecedented income inequality. The division between labor and capital smears — labor being Data Serfdom and capital, the notion of a digital platform. The only difference between Gilded Age 1.0 and now?

Where the heck are our railway riots?

While nearly two square miles of Pittsburgh went up in flames the summer of 1877, the riots represented the collective power of workers we celebrate on Labor Day each year. Sure, Occupy Wall Street made a few waves, but the current politics of our time have left us so divided, that we are paralyzed in the face of entrepreneurial conquerors.

Monopolies (our natural state, according to Peter Thiel and others) again rule our most important industries, whether they be information (Google), agriculture (Monsanto), or e-commerce (Amazon).

The industrial barons of late have yielded to new lords of information — Gates, Bezos, and Zuckerberg have replaced Carnegie, Frick, and Mellon.

Now that I live across the Eastern Peninsula, the name Carnegie has a different ring to it, literally, the name is pronounced carNEHgie. The different pronunciation brings a different connotation; I’ve become accustomed to hearing more tales of the ‘damn robber-baron’ than the ‘renowned robin-hood.’ For many, his philanthropy can’t account for the ruthless tactics, corruption, and vile treatment of workers that he employed to become the leader of the capitalist world.

However, missing from both portrayals of Carnegie, is his patronage of books. Before his death in 1919, he helped fund the creation of over 2,800 libraries across the world — constituting the largest individual investment in public libraries in American history.

How fitting then, that the current world’s richest man picked up right where Carnegie left off — beginning his own empire through the creation of the largest virtual library: Amazon. Carnegie and Bezos, self-made sons of immigrants, rose from humble beginnings through their insatiable thirst for knowledge. Bezos, like Carnegie, is criticized for the same capitalist tendencies: ruthlessly competitive work environments and squeezing every ounce of labor out of his factory workers.

Should they be blamed for fulfilling the requests of an ever-accelerating train of American consumerism?

All told, Andrew Carnegie eventually gave away roughly 90 percent of his personal fortune during his lifetime. Jeff Bezos is more than halfway to Carnegie’s 300 billion (in today’s dollars) and is already putting the fortune to use (see- purchase of Washington Post). His dollars, along with the growing number of billionaires of our time, will have the power to shift policy, our environment, and our world.

Jeff Bezos has attempted to mitigate concerns about his empire by ‘inverting’ the traditional org-structure pyramid to place himself at the bottom, and his ‘fulfillment associates’ (factory workers) at the top. In Carnegie’s pyramid, the machinations of many propped up one man’s fortune. In Bezos’s, one man’s machinations prop up the livelihoods of many. Neither pyramid scheme appears very stable. Inverted or not, the pyramidal structure of organizations and societies has been around for longer than the great pyramids of Egypt. But is the world ready for a flat-structured circle?

Whether or not you believe that the power law (the Pareto principle, Zipf’s law, etc.) governs the universe, we need to understand that access to the means of sustaining good health, the opportunity to learn from the wisdom accumulated in our culture, and the expectation that one may do so in a decent home and neighborhood are not privileges to be reserved for the few who were smarter than the system. We need to collectively acknowledge the way automation is exponentially rendering human work useless, making the powerful few, fewer and more powerful.

After nine months working in the technology space, I no longer think the answer is to stagnate innovation, and legislate against technology. At the end of the day, the manufacturing and trucking companies I work with are just trying to keep up with their neighbors in the same way big tech ruthlessly competes for our consumer data, and humans compete to work at the big tech companies. If my company decides we’re not going to provide the necessary software, our clients will be forced to go with an alternative provider or get eaten by a bigger shark.

As a product manager, I’m often referred to as the CEO of our product. Some days I question my relevance. Would there be anarchy in my absence, or am I merely a face for the product’s success and a scapegoat for its shortcomings?

While I don’t remember the exact concert at Carnegie Hall with my mother ten years ago, I can say that at one moment the musicians were perfectly silent. The conductor looked at the strings, then the flute section, raised his baton and the symphony commenced. In our current world, it is hard to imagine a harmonious orchestra without a conductor, a functioning product without a product manager, a winning sports team without a coach, and a successful company without a CEO.

As the early waves of decentralization wash onto our shores, it will be interesting to see how the symphonies of our time sound– can they stay in tune?